Political Dynasty Ban Debate: Where Should the Line Be Drawn in the Philippines?

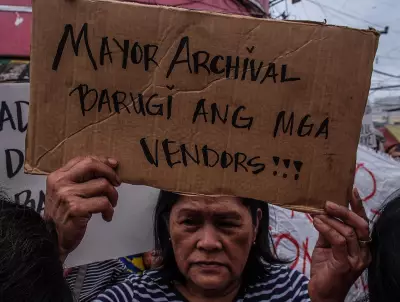

Nearly four decades have passed since the ratification of the 1987 Constitution, which explicitly prohibited political dynasties in the Philippines. Yet, these family-based political networks continue to dominate the nation's political landscape and are frequently implicated in severe corruption scandals, including the trillion-peso flood control controversy.

The Constitutional Provision and Its Limitations

Article II, Section 26 of the 1987 Constitution states, "The State shall guarantee equal access to opportunities for public service and prohibit political dynasties as may be defined by law." The inclusion of the phrase "as may be defined by law" rendered this provision non-self-executory, meaning it requires an enabling law from Congress to take effect.

To this day, no comprehensive anti-dynasty law has been passed by Congress. Christian Monsod, a member of the Constitutional Commission that drafted the charter and former chairman of the Commission on Elections, expressed regret, stating, "We overestimated the spirit of EDSA and underestimated the greed of our lawmakers." He referred to the EDSA People Power Revolution of 1986, which ousted a dictator, hoping it would curb dynastic politics.

Existing and Proposed Legislative Measures

Currently, the only existing ban is under Republic Act No. 10742, the Sangguniang Kabataan Reform Act of 2015, which prohibits relatives up to the second degree of consanguinity from running in youth council elections. However, broader proposals are now on the table:

- Senate Bill No. 18 by Senator Robin Padilla and Senate Bill No. 1548 by Senator Risa Hontiveros propose banning political dynasties up to the fourth degree of consanguinity or affinity.

- Bills by Senate President Pro Tempore Panfilo Lacson, Senator Erwin Tulfo, and Senator Francis Pangilinan advocate for a ban up to the second degree.

- Senator Benigno Paolo Aquino IV supports a prohibition up to the third degree.

In the 20th Congress, at least 21 bills in the House of Representatives and six in the Senate target political dynasties, though all remain at the committee level.

Defining Consanguinity and Affinity

Understanding these degrees is crucial to the debate:

Consanguinity refers to blood relationships:

- First degree: Parents and children.

- Second degree: Grandparents, siblings, and grandchildren.

- Third degree: Great-grandparents, uncles/aunts, nieces/nephews, and cousins.

- Fourth degree: Great-great-grandparents, great-aunts/uncles, first cousins, and grand-nieces/nephews.

Affinity involves relationships by marriage:

- First degree: Spouses.

- Second degree: Parents-in-law and children-in-law.

- Third degree: Grandparents-in-law, grandchildren-in-law, and siblings-in-law.

- Fourth degree: Great-grandparents-in-law, aunts/uncles-in-law, first cousins-in-law, and nieces/nephews-in-law.

Expert Opinion and Future Prospects

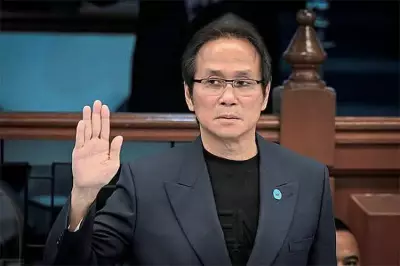

During a Senate hearing on February 4, 2026, Christian Monsod endorsed a ban up to the fourth degree of consanguinity or affinity for local, national, and party-list elections. He argued that the Philippines has suffered immensely due to entrenched political dynasties, describing the system as "feudalistic" and calling for its dismantling.

However, the critical question remains: Can such a law pass in a Congress dominated by political dynasties themselves? The ongoing legislative stalemate highlights the deep-rooted challenges in reforming the political system, as families in power resist measures that could undermine their influence.